As early-career researchers, one of the first things we are told about publishing is not to release our research as part of an edited volume. Chapters in edited volumes are not nearly as valued for career progression as journal articles, even though they may take the same amount of time and care to produce. When I edited a volume on open research data a few years ago, the most common reason for declining to submit a chapter was that it would simply not be valued for career purposes.

But people are clearly still publishing edited volumes. A report published today by the British Academy about open access and edited collections illustrates that roughly a quarter of humanities submissions to the 2014 REF were chapters in edited volumes, and for Classics this percentage was over 37%. I’m not sure how to square this with the (admittedly anecdotal) career advice given above. Perhaps these chapters are not as well-performing in the REF, maybe they aren’t submitted by early-career researchers, or maybe the advice is simply wrong in a UK context?

Whatever the truth of the matter, it seems apparent to me that edited volumes are valued despite their fraught relationship with career progression for early-career researchers. I read and cite a lot of work in edited collections and they can be a really helpful way of serendipitously finding content related to what you’re studying. With good editorial oversight, the chapters within edited volumes can also be more approachable and better contextualised than a special issue of a journal or equivalent.

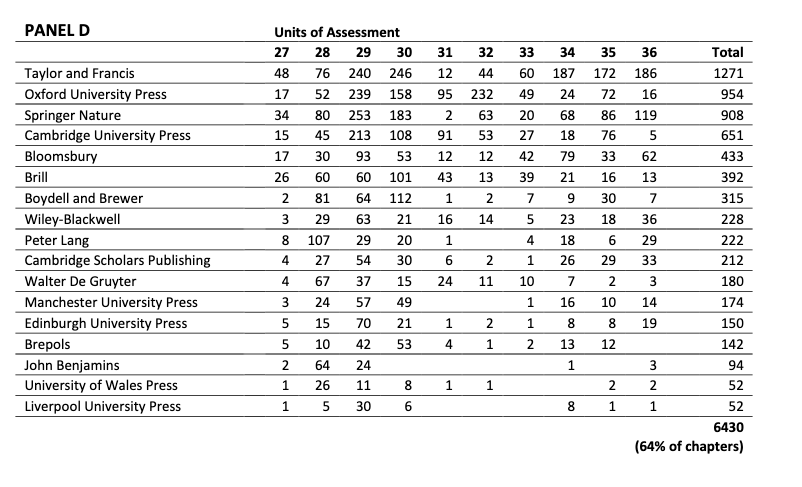

But what interests me is who is publishing these edited volumes. For those chapters submitted to the REF Panel D, the following publishers are listed in order of total submitted (reproduced under CC BY-NC-ND):

The vast majority are published by large commercial presses (and I include OUP and CUP here) and the minority are published with smaller commercials and UK university presses.

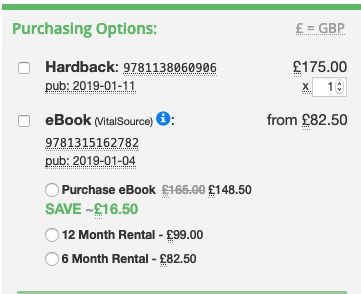

Yet if we take a look at the kind of edited volume being published by Routledge (part of the Taylor and Francis group), we see a £175 price tag on the hardback and £148.50 on the ebook, though you can rent the ebook for 6 months for only (!) £82.50:

The ‘handbook’ series is a specific kind of edited volume that is often expensive to purchase but can have quite a broad appeal (as the British Academy report highlights). And although I am not saying the price is representative of all edited collections published by commercial publishers, it seems to be a common strategy to produce edited volumes with the sole intention of selling them at inflated prices to libraries.

This is a real bugbear of mine. Edited volumes are exactly the kinds of titles that could be published with new, experimental, scholar-led, open-access publishers or basically anyone but a large commercial publishing house charging £150 for an ebook! If we assume that edited collections have a broad appeal and that they are published despite not being highly valued for career reasons, then this seems a pretty good argument for eschewing traditional, ‘prestigious’ toll-access publishers in favour of scholar-led and new university presses. This is a low-risk way for scholars to publish open access and support a more ethical and biblio-diverse publishing ecosystem in the process.

I am aiming this post at OA advocates in the humanities and social sciences who are looking for a way to publish OA and support alternative publishing projects. If you are going to publish an edited volume, I strongly urge you to not do so with a publisher that is going to charge £175 for a print volume. Instead, use the freedom you have to contribute your research to the growing corpus of work released by those pushing for a more ethical publishing future. The Radical Open Access Collective is a good place to start.