Today Janneke Adema and I published a new article in the journal New Formations entitled ‘‘Just One Day of Unstructured Autonomous Time’: Supporting Editorial Labour for Ethical Publishing within the University’. The article will be available in our repositories but is also currently freely accessible via the New Formations site: https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/newformations/vol-2023-issue-110/abstract-9909/ (although I’m not sure for how long!) The article is part of a special issue on the topic of public knowledge.

Should open access be removed from REF requirements?

In the past week, three senior research strategy figures at the University of Oxford have called for removing the open access ‘burden’ from the rules for the next Research Excellence Framework (REF). For the past REF excercise, open access has been a requirement for all submitted journal articles and UKRI are also now consulting on plans to include books within the rules for the next exercise. The Oxford authors make a number of points that the REF open access rules are bureaucratic, not commensurate with value and work against the broader adoption of open research practices through a narrow focus on open access. This is a significant statement from a UK university and represents a more combative attitude towards open access than we have seen in recent years.

In a subsequent article, Research Information presented a series of responses from influential figures within research culture and open research, all of whom were highly critical of Oxford’s intervention. Sally Rumsey, former head of scholarly communications at Oxford, described it as ‘short-sighted’ while Dorothy Bishop emeritus professor at Oxford considered it a ‘“a retrograde step to question benefits of open access”. Stephen Curry of the Research on Research Institute said: “If Oxford was looking to burnish its reputation as a defender of the status quo with this blogpost, then it has succeeded admirably.”

I think it’s helpful to have a conversation about whether the REF OA rules are still fit for purpose. To be sure, I’m not against OA in any way whatsoever, but I have been consistently critical of the burden of OA compliance. With reference to interviews with librarians and policymakers, my PhD thesis explored how the UK open access policy landscape created a culture of compliance that libraries were meant to orchestrate, in some cases forcing them to redirect staff from library publishing towards the REF policy. This burden was in addition to the fact that mandating open access via an increasingly bureaucratic set of regulations is not a particularly good way of getting researchers on board with broader cultures of openness. We still see a huge amount of apathy or antagonism to open access because of this.

Much has changed since my research was conducted and compliance is now firmly embedded within the UK library sector. Many open access library teams are organised according to a function of getting papers into repositories, ensuring deposit regulations are followed and advising researchers on what they should do to comply. This requires significant expertise in funder policy within a service that seeks to deposit as many of an institution’s papers as possible. This service operates in parallel with a more general approach to open access that seeks to shift subscriptions over to agreements with publishers that offer access to read content and the ability to publish bundled into one cost.

You might think that, with my general dislike for compliance-based approaches, I’m in favour of the Oxford authors’ proposals to remove the OA component from the REF. While I think it’s a good conversation to be having, I would caution against removing the requirement entirely. For journal articles, the UK university sector has taken great strides towards open access policies based on rights retention. These policies set the default for research to be made open access through repositories and allow authors to opt out if they would prefer to keep it closed. The UK university sector is technically and infrastructurally well prepared to make all journal articles OA in both green and gold forms, while also seeking to nurture an ecosystem of community-led and innovative models for no-fee OA. This perhaps could mean that a more relaxed requirement is needed, one that does not require all individual papers to be checked for compliance but assumes a general position of good faith that universities will make their research openly accessible through rights retention policies. This means that I would be interested in a discussion around relaxing the OA requirement for journals rather than removing it entirely. Any money saved on compliance could then be reinvested in experimentation with open research practices and long-form scholarship, something the Oxford authors tacitly support although fail to make a strong case for.

This is a delicate argument because the UKRI’s approach to OA has simultaneously enabled more OA through compliance but also more capacity for ethical forms of OA through its block grant that can be spent on a broader range of infrastructures and staff time in service of OA in the UK. Compliance is very much a feature of UK OA, but so are initiatives like the COPIM project, Open Library of Humanities, and a host of new OA university presses. My argument stems from the fact that we should continue to support these kinds of projects while paying less attention to compliance-based approaches without removing the general need for institutions to make all their research OA. The UK is in a very good position to adopt this stance.

So I would have liked the Oxford authors to have made more of an argument around the benefits of open research and the ways to stimulate open practices, which they say are held back by the REF policy, as a way of working through compliance towards more ethical and pluralistic publishing futures. Without this argument, you end up opening the door to more conservative voices that seek to return to the halcyon days in which public access was not a concern, as is the case with Rick Anderson’s piece in the Scholarly Kitchen blog. Here, Anderson argues that we should remove the ‘ideological orthodoxy’ of open access requirements and instead allow researchers to ‘exercise their own judgment’ around open access, in an ironic appeal to an Americanised ideological orthodoxy of individual freedom. Fortunately for us over the pond, we have a chance to care about and nurture the broader collective benefits of open access.

Research integrity, preprints and where should the responsibility lie?

Last week, The Scholarly Kitchen posted an article by Angela Cochran,Vice President of Publishing at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, about the inability of publishers to deal with research fraud. She writes:

“The bottom line is that journals are not equipped with their volunteer editors and reviewers, and non-subject matter expert staff to police the world’s scientific enterprise.”

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2024/03/28/putting-research-integrity-checks-where-they-belong/

Cochran’s argument is that although publishers manage the peer review process, it was never an expectation of peer review that they would perform ‘forensic analysis’ of datasets and associated materials. Given the huge amount of fraud currently being discovered, and presumably the huge amounts of fraud that is also undiscovered, publishers and their academic volunteers do not have the resources to police the scientific literature. Instead, Cochran writes, ‘every research article submitted to a journal should come with a digital certificate validating that the authors’ institution(s) has completed a series of checks to ensure research integrity.’ The work of research integrity should therefore fall on universities rather than the publishing industry.

Naturally, many scientists jumped on this piece as an example of the publishing industry looking to externalise costs in order to maintain their margins, much like they do with the reliance on volunteer academic labour. For the fraud detector, Elisabeth Bik, the piece sounds like Boeing saying ‘you know how much money quality control costs???‘. While the piece does read like a publisher trying to shift blame for something for which they should be at least partly responsible, Cochran makes the equally correct point that there has not been enough attention paid to the role of universities in research integrity scandals.

I’m interested in the proposal that universities take on more of a role of assessing publications prior to formal dissemination. In fields such as high-energy physics, institutions organise quite rigorous internal review processes between large research teams, a practice that facilitated the dissemination of preprints and led to near-universal open access to high-energy physics research. There is absolutely no reason why universities could not organise such processes for other disciplines too.

With preprints in the news this week thanks to the recently updated Gates policy — which no longer requires publication in a journal but does require that authors share a preprint of their research — the proposal for universities to assess research prior to formal journal submission is attractive because it facilitates immediate sharing while adding a layer of trust to the content through an internal review process that is standardised across institutions and operates between them. This practice will in turn encourage researchers to preprint their research because it will become both normalised and will offer a baseline level of verification that the work can be shared.

I’m not making a proposal here for a specific kind of review process, only that arranging such a process before dissemination is both achievable and desirable. It speaks to the idea that preprints require a degree of structure and labour that I think is often ignored by open science advocates, while also positioning research dissemination under the control of research communities rather than commercial publishing houses extracting our free labour and content. Bringing research dissemination back in house in this way is one way of reducing the market-driven incentives that harm scholarly communication. Yet the idea still recognises the intentional work needed to disseminate good research: i.e., all technical or platform-based solutions will fail if they do not take into account that this work needs to be done.

When I propose bringing publishing back under researcher control in this way, someone always chimes in with the idea that neoliberal universities themselves are essentially businesses too and so cannot be relied upon to adequately vet their work in the way described. This is why such an idea has to be researcher-led, not managerial, and a collaboration between institutions (much like our friends in high-energy physics). I am not proposing that universities bluntly “vet” their own research, but rather that experimentation with intra- and inter-institutional review processes is an excellent way to both encourage rapid dissemination of research while taking publishing back from an industry that seems largely hellbent on running scholarly communication into the ground through APCs and money-saving automation.

To come full circle, I think that academic societies are actually in a good position to both advocate for and organise the kinds of processes I’m describing, theoretically at least. Clearly many of them are completely wedded to the traditional commercial publishing models from which they fund their activities, but many of them are not and so have the ability to experiment with how they organise their different approaches to research communication. Societies can reflect a kind of collectivity that is so needed in higher education right now, while also providing the practical forms of governance to effect real change.

Nothing to lose but our tiny royalty cheques: on the proposed open access books policy for the next REF

Open access policy mandates have never been an effective way of convincing researchers of the benefits of exploring alternative, open publishing practices. Forcing someone to do something will not help them engage with the reasons for doing it. Instead, the mandate feels like a simple tickbox exercise that can be ignored once fulfilled. Apathy and begrudging acceptance have been the response of many researchers to the open access policy of the Research Excellence Framework, which many see as a top-down imposition with which they comply just to get their head of department off their back.

Last week, UKRI announced its proposed updates to the open access policy for the next REF, which now includes monographs and other book-based outputs including edited volumes and scholarly editions (but not, despite the initial confusion, trade books). All eligible books submitted to the REF that are under contract from January 2026 would have to be made openly available no later than two years after publication (either in a repository or the final version of record on the publisher’s site). UKRI are currently consulting on these proposals and they are not set in stone.

To be sure, this is a gentle policy for which no additional funds have been earmarked by UKRI. In a recent article for Times Higher Education, Steven Hill, chair of the REF 2029 steering group, commented that “the proposed policy for monographs is permissive of a range of routes to open access, some of which have low or zero upfront costs.” A two-year embargo is something that can be negotiated with a publisher at the contract stage. Ideally, the final version of record would be deposited in the repository — buoyed by arguments that immediate open access does not negatively impact sales — but the final accepted version is also acceptable to UKRI. This is all possible with no fees being paid to the publisher, but it does require the publisher to prioritise their commitment to the scholarly community over a shorter term focus on commercial returns.

Yet in the same THE article, we also see responses by researchers worried about losing “career-making opportunities” or about universities “rationing who gets to write books”. Richard Carr writes that the policy would:

lead to hundreds of thousands of pounds universities don’t really have being transferred to private publishers…and won’t achieve anything that mandating a free public facing blog or two outlining said output’s content/impacts wouldn’t”

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/forget-book-deals-if-ref-open-access-rules-proceed-warn-scholars

Again, forcing researchers to do something is a sure way of getting them to push back on it, not least when it’s tied to the much-loathed Research Excellence Framework. Yet it’s troubling how these over-the-top reactions in THE article are couched in a logic of self-interest that entirely ignores the possible benefits not just of open access but of working towards more ethical publishing practices more generally. These responses, primarily coming from senior figures in the humanities and social sciences, arise from a position that does not consider the need to make radical changes to publishing behaviours for the collective good.

This is what I find most frustrating with the responses based on the fact that researchers will now have to start paying high BPCs or lose book contracts is that it is a purely defensive argument grounded in self-interest and conservatism (nor is it even accurate). A lot of the discussion on social media also centered on annual royalties, which for academics are minimal and would almost certainly be untouched under the current OA policy.

Lucy Barnes wrote an excellent Twitter thread on the myths that were circulating about open access books, which you (hopefully if I can still embed tweets) read here:

Lucy also helpfully points to the rich ecosystem of open access presses that do not charge BPCs. Many of these are researcher-led and many are based within universities. They are part of our research communities and are our colleagues, not private companies looking to funnel off cash from our free labour and content. University presses will also grant requests to make an embargoed version of the book open access; it just takes a conversation rather than an automatically defensive approach that they will refuse you.1 Publishing with these presses contributes to a much better culture of knowledge dissemination than the BPC-led cultures of commercialised presses.

So these kinds of overreactions to a pretty gentle open access books policy betray something much greater about the state of arts, humanities and social sciences in the UK. By all means push back on the cultures imposed by policy instruments like the REF, but do so from a position that wants to stimulate solidarity and a collectivising response to the current brutal assault on our disciplines in the UK. Open access book publishing done correctly does help us work towards a more ethical way of producing and sharing knowledge. It can allow us to stimulate new forms of authorship, explore collective forms of feedback and dissemination, and experiment with what the book even is in a digital age. While these practices are not present within the REF policy, they are not entirely absent from it either.

Clearly the REF contributes to the logic of individualism I am writing against, but that does not mean we can’t use its requirements to nurture better cultures of publishing for our communities. As we have increasingly outsourced knowledge production processes (and career decisions) to a commercial publishing industry, shouldn’t we be looking for reasons to return scholarly communication to research communities and away from the hands of the market all while making our research freely available to anyone who wants access? Probably…

- My forthcoming book with University of Michigan Press will be published open access with no fees. MIT Press will offer the same. ↩︎

What’s so bad about consolidation in academic publishing?

Today’s Scholarly Kitchen blog post is an attempt by David Crotty — the blog’s editor — to quantify the increasing consolidation of the academic publishing industry. Crotty concludes:

Overall, the market has significantly consolidated since 2000 — when the top 5 publishers held 39% of the market of articles to 2022 where they control 61% of it. Looking at larger sets of publishers makes the consolidation even more extreme, as the top 10 largest publishers went from 47% of the market in 2000 to 75% in 2023, and the top 20 largest publishers from 54% to controlling 83% of the corpus.

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2023/10/30/quantifying-consolidation-in-the-scholarly-journals-market/

It’s helpful to have more data on the increasing power that a small number of academic publishers hold. Crotty charts this consolidation from the year 2000 onwards, from the concentration brought about by the effects of the Big Deal to the present day where 5 publishers now control 61% of the article output, brought about by the dominant business models for open access based on greater volume and technological scale. The author’s finger is pointed at Coalition S for instigating a ‘rapid state of change’ that allows author-pays open access to flourish.

I’m no fan of open access policies, Plan S especially, and I’m sure that policy interventions play a part in the consolidation at play. There are of course many ways of achieving open access without recourse to author fees, transformative agreements, or technologies that remove human expertise in place of automation and scale. But while there is nothing natural or necessary about the relationship between open access and consolidation, there is a much stronger connection between commercialisation and consolidation. The recent history of academic publishing has been of marketisation and, hence, consolidation.

I always bristle when I read that open access is to blame for the problems with the publishing market, not simply because open access does not have to be a market-based activity (and is better when it isn’t) but more because the explanation is so shallow. It is a position that usually takes as its starting point that the natural and proper way for academic publishing to be organised is as a commercial activity and any intervention that works against this is to blame for the deleterious effects of commercialisation. Publishing is and always is a business (possibly a reflection of the constituents that the Scholarly Kitchen represents), despite the fact that it is exactly the commercial nature of publishing that is the problem.

Yet open access is good precisely because it allows us to reorient academic publishing away from commercial practice and to experiment with forms of publishing that are less reliant on competition, profiteering and the extraction of free and under-remunerated labour. Policymakers are starting to wake up to this fact, as in part illustrated by the turn towards no-fee and non-commercial forms of open access, and I am cautiously optimistic about this turn. The danger is that policymakers mandate no-fee open access in accordance with the requirements of commercial publishing and the need to devalue skilled labour in the pursuit of revenue.

So it’s easy to criticise open access policies for their harmful impact, but this has to be done from a position that understands how the same issues of profiteering and extraction were a consequence of the subscription market too. They are the logical extension of publishing as a market-based activity, not of wanting to make the literature freely available to all. Open access policies do not address the problem of marketisation largely because they are not designed to do so. Profit-seeking actors create business models to maximise their revenues as a result of such policies. The whole system rests on this logic of extraction and that’s what needs to be opposed.

How to cultivate good closures: ‘scaling small’ and the limits of openness

Text of a talk given to the COPIM end-of-project conference: “Scaling Small: Community-Owned Futures for Open Access Books”, April 20th 2023

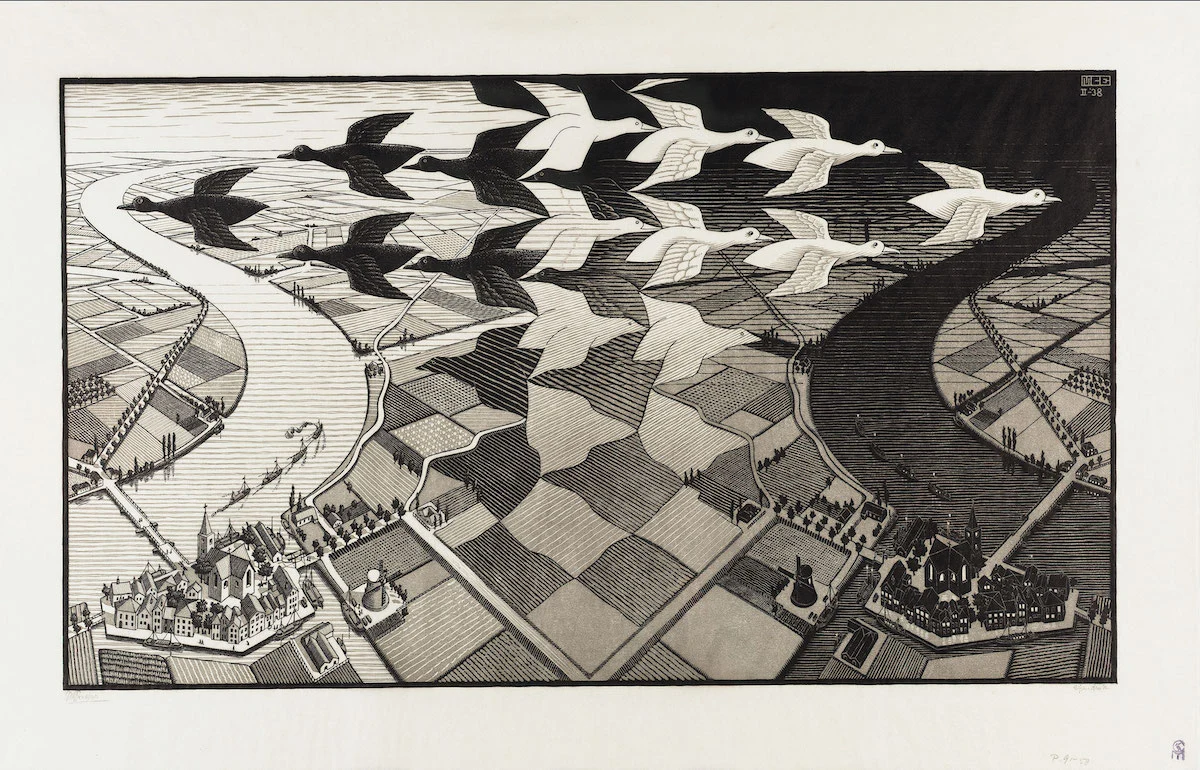

Open access publishing has always had a difficult relationship with smoothness and scale. Openness implies seamlessness, limitlessness or structureless-ness – or the idea that the removal of price and permission barriers is what’s needed to allow research to reach its full potential. The drive for seamlessness is on display in much of the push for interoperability of standards and persistent identifiers that shape the infrastructures of openness. Throughout the evolution of open access, many ideas have been propagated around, for example, the necessity of CC BY as the one and only licence that facilitates this interoperability and smoothness of access and possible reuse. Similarly, failed projects such as One Repo sought to create a single open access repository to rule them all, in response to the perceived messy and stratified institutional and subject repository landscape.

Yet this relationship between openness and scale also leads to new kinds of closure, particularly the commercial closures of walled gardens that stretch across proprietary services and make researcher data available for increasing user surveillance. The economies of scale of commercial publishers require cookie-cutter production processes that remove all traces of care from publishing, in exchange for APCs and BPCs, thus ensuring that more publications can be processed cheaply with as little recourse to paid human labour as possible. Smoothness and scale are simply market enclosures by another name.

When Janneke and I were writing our ‘scaling small’ article, we were particularly interested in exploring alternative understandings of scale that preserve and facilitate difference and messiness for open access book publishing. How can we nurture careful and bibliodiverse publishing through open access infrastructures when it is exactly this difference and complexity that commercial forms of sustainability want to standardise at every turn? In outlining ‘scaling small’, we looked to the commons as a way of thinking through these issues.

As a mode of production based on collaboration and self-organisation of labour, the commons was a natural fit for the kinds of projects we were involved in. We charted the informal mutual reliance – what we referred to as the latent commons, borrowing from Anna Tsing (2017) – within the Radical Open Access Collective right through to the expansive formality of the COPIM project. In doing so, we illustrated the different forms of organisation that facilitate alternative publishing projects that stand in opposition to the market as the dominant mode of production. Scaling small is primarily about how open access can be sustained if we embed ourselves in each other’s projects and infrastructures in a way that has ‘global reach but preserves local contexts’ (Adema and Moore 2021). It is a reminder that the commons is an active social process rather than a fixed set of open resources available to all.

In their posthumously released book On the Inconvenience of Other People, Lauren Berlant writes against a fixed understanding of the commons that ‘merely needs the world to create infrastructures to catch up with it’ (Berlant 2022). Instead, for Berlant, the ‘better power’ of the commons is to ‘point to a way to view what’s broken in sociality, the difficulty of convening a world conjointly’. From our perspective, the commons is about revealing how hard it is to scale small in a world dominated by the need for big, homogenising platforms. It is not, then, about having a fixed understanding of the infrastructures necessary for open access publishing but more about experimenting with the different kinds of socialities that may allow experimental infrastructures of different scales and formalities to flourish.

This is why scaling small reveals the limits of openness and forces us to instead cultivate good closures (echoing the ‘good cuts’ of Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska’s (2012) reading of Karen Barad) based on what we want to value ethically and politically. So rather than leaving everything to the structureless-ness of market-centric openness, through COPIM we learn how to deal with the fact that things like governance, careful publishing and labour-intensive processes do not scale well according to economic logic. In my time on the COPIM project, for example, I learned how community governance requires pragmatic decision-making and norms of trust within the community; it is not something that can be completely organised through rules and board structures. Yet we still proceed to build these structures to see what works and what doesn’t, relying on the fact that we all share a broad horizon of better, more ethical futures for book publishing.

Yet of course, antagonism still exists within and outside the COPIM project. Is it OK that the models and infrastructures being developed within this community are being extracted from it by commercial publishers? Bloomsbury, for example, has just proudly announced it is the first commercial book publisher to utilise the kind of collective funding model being developed by COPIM, Open Library of Humanities, and other scholar-led publishers. How is it possible to scale small when a big commercial actor is waiting to take what you have developed and piggyback on it for commercial gain? Do we engage with commercial publishers or keep them at arms’ length?

Again, part of the answer to this question lies in sociality, or the fact that COPIM has managed to carve out a pretty unique situation in neoliberal higher education that has brought together a vast array of likeminded people and organisations with an explicit goal of undermining the monopolisation of commercial publishers in place of community-led approaches. Coupled with the move to diamond open access journals that is gaining traction particularly in continental Europe, we have an important counter-hegemonic project being formed around communities cross-pollinating with one another rather than competing. Commercial publishers may treat COPIM’s work as free R&D but it cannot extract the social glue that keeps it together and sets it apart from marketised models.

This is why I am so excited about the recent announcement of Open Book Futures and its potential to further reach out to and engage libraries, infrastructure providers and communities outside the Global North, increasing the messiness that allows us to scale small. As someone now working in one, I am especially pleased to see libraries treated as partners rather than a chequebook – as is too often the case with new open access initiatives – and given meaningful governance over the future of the Open Book Collective. Scaling small will only work if libraries are understood as part of the community and part of the cross-pollination at work. Without this, there is a danger that the additional labour of collections librarians is undervalued or objectified as a tool for the provision of open access, even though it is a crucial and active facilitator of the smallness we desire.

As an interdisciplinary, multi-practitioner group of advocates for better publishing futures, I hope we can also consider how scaling small may help transform our professional networks away from the commercially driven conservatism of learned societies and towards expansive forms of mutual reliance and care within and between them. In doing so, it can help build the necessary chains of equivalence between previously disparate learned societies and member organisations, allowing us to turn our attention to the brutally individuating structures of marketised academia (which, at bottom, is the bigger issue at hand).

So in conclusion, I hope to have conveyed in these short remarks that scaling small is, above all, a project of sociality, building new connections and getting together in different ways, and not simply or even primarily about the publications and resources being produced and shared. The point is to continue learning how to hold onto this social and biblio-diversity through the decisions we take and the institutional closures we enact, particularly as more and more actors become involved. Viewed in this light, scaling small reveals the limits of openness and the necessity of cultivating good closures with other (inconvenient) people.

Work cited:

Adema, Janneke, and Samuel A. Moore. 2021. ‘Scaling Small; Or How to Envision New Relationalities for Knowledge Production’. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.918.

Berlant, Lauren. 2022. On the Inconvenience of Other People. Writing Matters! Durham: Duke University Press.

Kember, Sarah, and Joanna Zylinska. 2012. Life after New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2017. The Mushroom at the End of the World On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Preprints and the futures of peer review

Yesterday, the preprint repositories bioRxiv/medRxiv and arXiv released coordinated statements on the recent memo on open science from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. While welcoming the memo, the repositories claim that the ‘rational choice’ for making research immediately accessible would be to mandate preprints for all federally funded research. They write:

This will ensure that the findings are freely accessible to anyone anywhere in the world. An important additional benefit is the immediate availability of the information, avoiding the long delays associated with evaluation by traditional scientific journals (typically around one year). Scientific inquiry then progresses faster, as has been particularly evident for COVID research during the pandemic.

https://connect.biorxiv.org/news/2023/04/11/ostp_response

This is familiar rhetoric and a couple of commentators on social media have noted the similarities between what the preprint servers are proposing here and ‘Plan U‘, the 2019 initiative that attempts to ‘sidestep the complexities and uncertainties’ of initiatives like Plan S through a similar requirement for immediate preprinting of all funded research. The designers of Plan U argue that preprinting is much simpler and cheaper because preprint servers do not perform peer review and so operate on a lower cost-per-paper basis.

I think it’s important to acknowledge the disciplinary differences when it comes to preprinting, not just that many scholars in the arts, humanities and social sciences are more reluctant to preprint, but also the fact that the tradition of preprinting referenced here emerged out of a particularly narrow set of disciplinary conditions and epistemic requirements in high-energy physics. While by no means the only disciplinary group to share working papers (see economics, for example), preprinting has a rich history in high-energy physics. This is primarily because of the ways in which HEP research projects are structured between large overlapping groups from a number of institutes, each with its own internal review and quality-control processes that take place before a preprint is uploaded to the arXiv. I discussed this more in a previous post on in-house peer review processes.

The reason I’m mentioning this is that the statement made by the repositories fails to account for one of the more important elements of Plan U: that such an approach will ‘produce opportunities for new initiatives in peer review and research evaluation’. The need to experiment with new models of peer review/research evaluation should be front and centre of any call for a new, open system of publishing, especially one predicated on lower costs due to the lack of peer review. Without well-explored alternatives, there is an implication that the online marketplace of ideas will just figure out the best way to evaluate and select research.

Yet the history of high-energy physics tells us that ‘openness’ should not be a free-for-all but is predicated on well-designed socio-technical infrastructures that evolved from and thus suit the discipline in question. But these infrastructures and new socialities need to be designed and implemented with care, not left for us to just figure it all out. This is why any system of publishing based on preprinting+evaluation needs adequate support to experiment and build the structures necessary for non-publisher-based forms of peer review. I’m convinced, for example, that a lot of this could be built into the work of disciplinary societies and in-house publishing committees. Yet these ideas require financial support to see what works.

In the context of the never-ending crisis in peer review, the OSTP memo could serve as a springboard for figuring out and operationalising new forms of research evaluation. This could make for a sensitive transition away from traditional publication practices that help the commercial publishing industry maintain control of scholarly communication. The memo is therefore a good opportunity to experiment and build entirely new approaches to academic publishing — but we have to make the correct arguments for how we figure this out, not arguments based on cheaper publishing and web-based editorial free-for-alls.

New preprint: the politics of rights retention

I’ve just uploaded ‘The Politics of Rights Retention’ to my Humanities Commons site: https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:52287/. The article is a preprint of a commentary currently under consideration for a special issue on open access publishing.

Abstract

This article presents a commentary on the recent resurgence of interest in the practice of rights retention in scholarly publishing. Led in part by the evolving European policy landscape, rights retention seeks to ensure immediate access to accepted manuscripts uploaded to repositories. The article identifies a trajectory in the development of rights retention from something that publishers could previously ignore to a practice they are now forced to confront. Despite being couched in the neoliberal logic of market-centric policymaking, I argue that rights retention represents a more combative approach to publisher power by institutions and funders that could yield significant benefits for a more equitable system of open access publishing.

The curious internal logic of open access policymaking

This week, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) declared 2023 its ‘Year of Open Science‘, announcing ‘new grant funding, improvements in research infrastructure, broadened research participation for emerging scholars, and expanded opportunities for public engagement’. This announcement builds on the OSTP’s open access policy announcement last year that will require immediate open access to federally-funded research from 2025. Given the state of the academic publishing market, and the tendency for US institutions to look towards market-based solutions, such a policy change will result in more article-processing charge payments and, most likely, publishing agreements between libraries and academic publishers (as I have written about elsewhere). The OSTP’s policy interventions will therefore hasten the marketisation of open access publishing by further cementing the business models of large commercial publishers — having similar effects to the policy initiatives of European funders.

As the US becomes more centralised and maximalist in its approach to open access policymaking, European institutions are taking a leaf out of the North American book by implementing rights retention policies — of the kind implemented by Harvard in 2008 and adopted widely in North America thereafter. If 2023 will be the ‘year of open science’ in the USA, it will surely be the year of rights retention in Europe. This is largely in response to funders now refusing to pay APCs for hybrid journals — a form of profiteering initially permitted by many funders who now realise the errors of their ways. With APC payments prohibited, researchers need rights retention to continue publishing in hybrid journals while meeting their funder requirements.

There is a curious internal logic here: the USA following the market-making of Europe, while Europe locking horns with the market and adopting US-style rights retention policies. Maybe this means that we’re heading towards a stable middle ground between the models of these two separate (but equally neoliberal) approaches, or maybe one of the hegemonic blocs is further along the road that both are travelling (not to mention the impact these shifts and market impacts have on Global South countries, or simply those outside Europe and North America).

Clearly I’m being too binary and eliding a great deal of complexity in this very short post, but it struck me that there is a curious internal logic at work here. The push for open access has forced a shift in the business models of academic publishers, but this very same shift causes more of the profiteering that open access was responding to in the first place. Policymakers dance back and forth trying to make open access workable for researchers and affordable for universities, but neither of these aims will be possible to achieve while researchers are required to publish in journals owned by a publishing industry more answerable to shareholders than research communities.

Research assessment in the university without condition

Cross-posted on the Dariah Open blog as part of their series on research assessment in the humanities and social sciences

In his lecture entitled ‘The future of the profession or the university without condition’, Jacques Derrida makes the case for a university dedicated to the ‘principle right to say everything, whether it be under the heading of fiction and the experimentation of knowledge, and the right to say it publicly, to publish it.’ (Derrida 2001). Beyond mere academic freedom, Derrida is arguing for the importance not just of the right to say and publish, but to question the very institutions and practices upon which such freedom is based – those performative structures, repertoires and boundaries that make up what we call (and do not call) ‘the humanities’.

One such structure – implicit in much of what Derrida writes – relates to the material conditions of the university, or the relationship between ‘professing’ and being ‘a professor’ tasked with the creation of singular works representing their thought (‘oeuvres’). Derrida identifies a gulf between the unconditional university he is arguing for and the material conditions that work against the realisation of such a university. Academics are conditioned to publish work in certain ways, not in the service of this unconditional university but in order to simply earn a living. Integral to this situation are the ways in which humanities research and researchers are assessed and valued by universities and funders. We publish in prestigious books and journals so that we might continue to ‘profess’ in the university for a while longer.

For the most part, research assessment reform promises to tinker with these structures and propose new ‘fairer’ ways to evaluate research. For example, the recent European agreement on reforming research assessment seeks to eradicate journal markers and inappropriate quantitative measures, while promoting qualitative measures that reward a plurality of roles and ways that academics can contribute to research. These recommendations are made in the service of recognising those ‘diverse outputs, practices and activities that maximise the quality and impact of research’ (p. 2). The implication is that good research is being done, but it is not possible to learn this from current approaches to research assessment. Assessment is conceived primarily as an epistemological issue that more accurately rewards those doing the best work.

Absent from these reforms is a thoroughgoing consideration of the fact that research assessment is, more than anything else, a labour issue. It is about the material conditions that allow participation and progression with higher education institutions. The mere fact that researchers chase prestige at every turn is because this is the path to being rewarded in such a brutally competitive academic job market. Without a greater push to end precarity and ease workloads, changing evaluative criteria will have no impact on the labour conditions within the contemporary university. This is why such reforms need to be coupled with a real commitment to improving labour conditions that will in turn have their own epistemological benefits in the form of less pressure to publish and a greater freedom to experiment.

I’m not here to propose alternatives to the European reforms. Instead, I want to us to consider whether Derrida’s university without condition – though no more than a theoretical construct – also requires us to refuse the conditions of external research and especially researcher assessment. Abandoning assessment could be undertaken in favour of careful and collectivising appreciation by the communities that create and sustain research. We should therefore take as our starting point that the assessment of research for the distribution of scarce resources is not strictly necessary to the pursuit of research. Clearly, financial resources have to be distributed, but a more equitable alternative would be to offer greater democratic governance by all members of the university over how resources are distributed: randomly, communally, through basic income or however else. This is the more urgent work of research assessment reform, not tinkering at the margins.

These more experimental approaches, although gaining traction, presuppose that the university should not be beholden to liberal ideas of meritocracy or individual excellence. Assessment reform should instead lower barriers to participation and facilitate experimental, diverse and collective approaches to knowledge production for their own sake. But it is this connection to the material conditions of labour that is most important to recognise and support: the university without condition requires it.

Work cited

Derrida, Jacques. 2001. ‘The Future of the Profession or the Unconditional University (Thanks to the Humanities That Could Take Place Tomorrow)’. In Jacques Derrida and the Humanities: A Critical Reader, edited by Tom Cohen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.