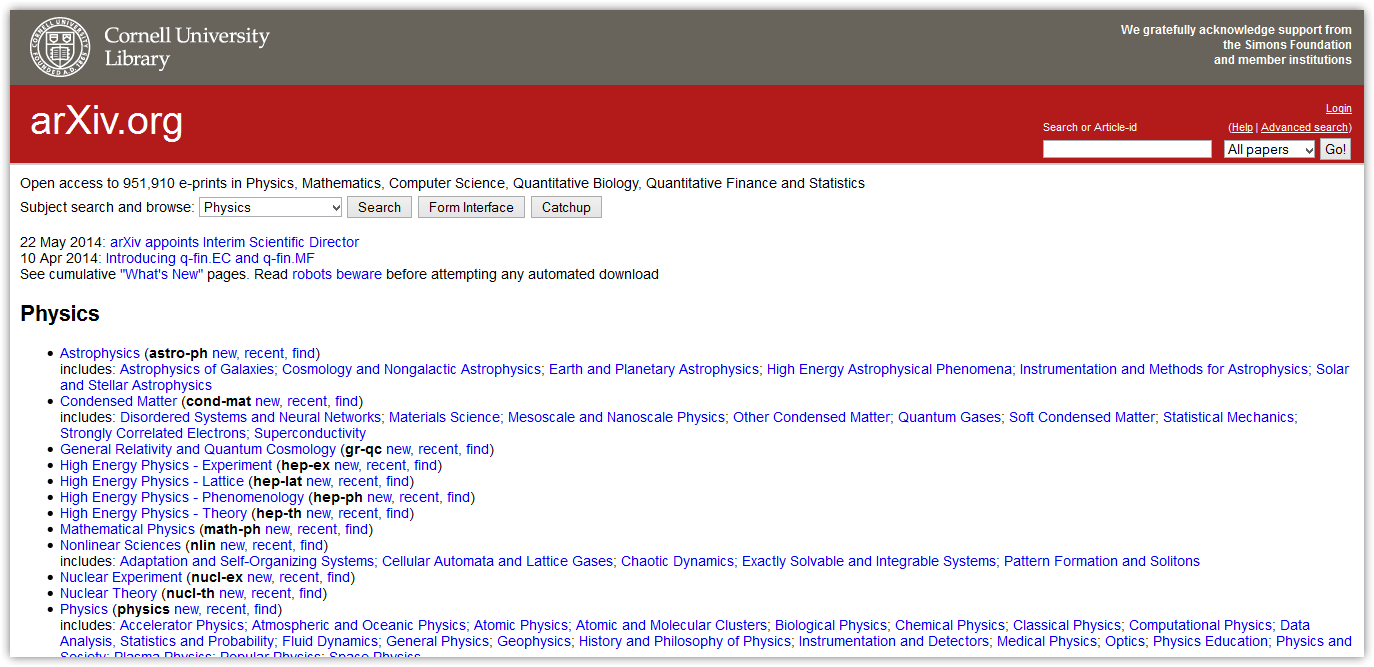

Yesterday, the preprint repositories bioRxiv/medRxiv and arXiv released coordinated statements on the recent memo on open science from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. While welcoming the memo, the repositories claim that the ‘rational choice’ for making research immediately accessible would be to mandate preprints for all federally funded research. They write:

This will ensure that the findings are freely accessible to anyone anywhere in the world. An important additional benefit is the immediate availability of the information, avoiding the long delays associated with evaluation by traditional scientific journals (typically around one year). Scientific inquiry then progresses faster, as has been particularly evident for COVID research during the pandemic.

https://connect.biorxiv.org/news/2023/04/11/ostp_response

This is familiar rhetoric and a couple of commentators on social media have noted the similarities between what the preprint servers are proposing here and ‘Plan U‘, the 2019 initiative that attempts to ‘sidestep the complexities and uncertainties’ of initiatives like Plan S through a similar requirement for immediate preprinting of all funded research. The designers of Plan U argue that preprinting is much simpler and cheaper because preprint servers do not perform peer review and so operate on a lower cost-per-paper basis.

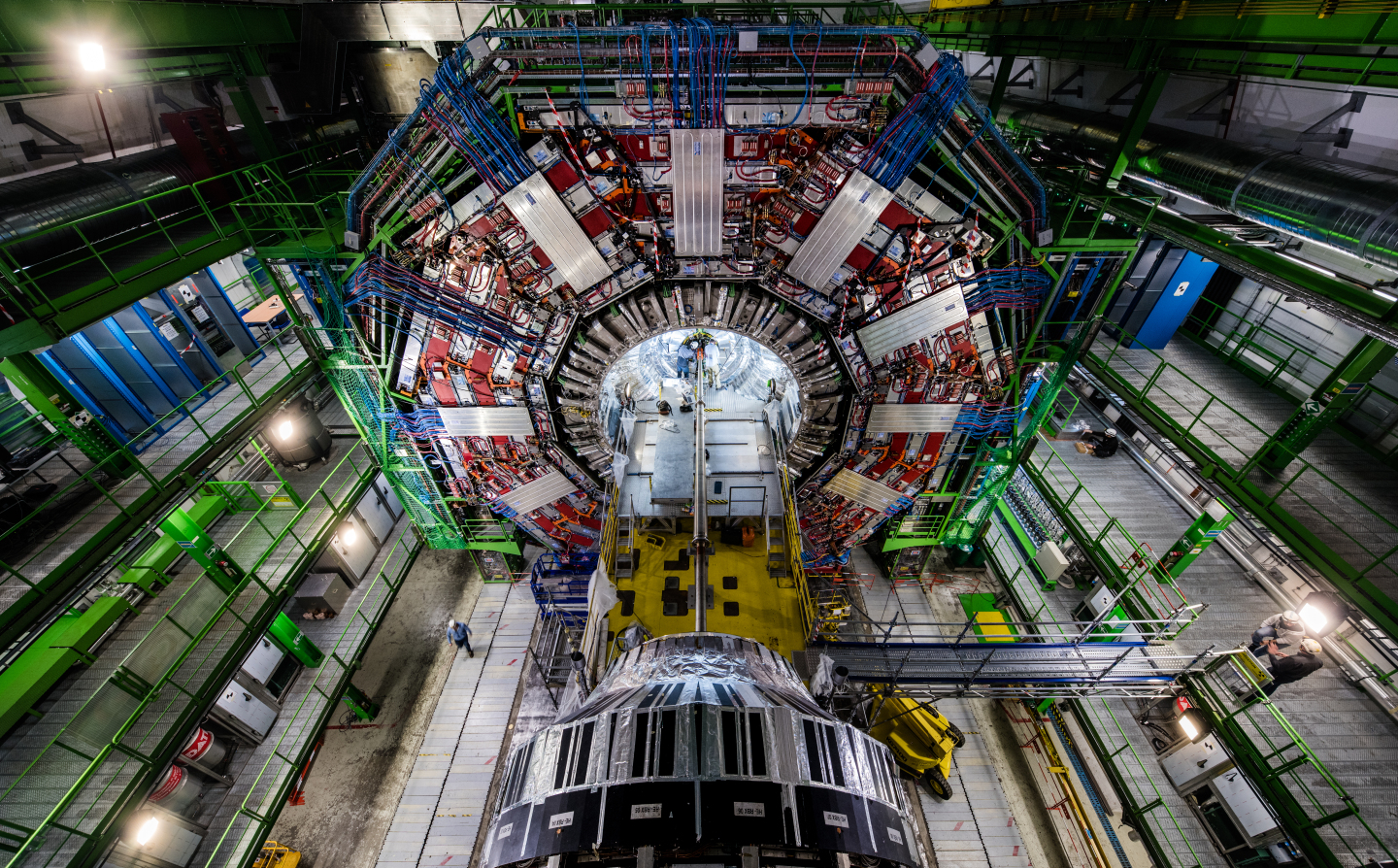

I think it’s important to acknowledge the disciplinary differences when it comes to preprinting, not just that many scholars in the arts, humanities and social sciences are more reluctant to preprint, but also the fact that the tradition of preprinting referenced here emerged out of a particularly narrow set of disciplinary conditions and epistemic requirements in high-energy physics. While by no means the only disciplinary group to share working papers (see economics, for example), preprinting has a rich history in high-energy physics. This is primarily because of the ways in which HEP research projects are structured between large overlapping groups from a number of institutes, each with its own internal review and quality-control processes that take place before a preprint is uploaded to the arXiv. I discussed this more in a previous post on in-house peer review processes.

The reason I’m mentioning this is that the statement made by the repositories fails to account for one of the more important elements of Plan U: that such an approach will ‘produce opportunities for new initiatives in peer review and research evaluation’. The need to experiment with new models of peer review/research evaluation should be front and centre of any call for a new, open system of publishing, especially one predicated on lower costs due to the lack of peer review. Without well-explored alternatives, there is an implication that the online marketplace of ideas will just figure out the best way to evaluate and select research.

Yet the history of high-energy physics tells us that ‘openness’ should not be a free-for-all but is predicated on well-designed socio-technical infrastructures that evolved from and thus suit the discipline in question. But these infrastructures and new socialities need to be designed and implemented with care, not left for us to just figure it all out. This is why any system of publishing based on preprinting+evaluation needs adequate support to experiment and build the structures necessary for non-publisher-based forms of peer review. I’m convinced, for example, that a lot of this could be built into the work of disciplinary societies and in-house publishing committees. Yet these ideas require financial support to see what works.

In the context of the never-ending crisis in peer review, the OSTP memo could serve as a springboard for figuring out and operationalising new forms of research evaluation. This could make for a sensitive transition away from traditional publication practices that help the commercial publishing industry maintain control of scholarly communication. The memo is therefore a good opportunity to experiment and build entirely new approaches to academic publishing — but we have to make the correct arguments for how we figure this out, not arguments based on cheaper publishing and web-based editorial free-for-alls.