On February 26th, what feels like a lifetime ago now, the Los Angeles Times published a column with the headline ‘COVID-19 could kill the for-profit science publishing model. That would be a good thing’. Its author, Michael Hiltzik, argues that for-profit publishing is ‘under assault by universities and government agencies frustrated at being forced to pay for access to research they’ve funded in the first place.’ Hiltzik doesn’t really go into how open access confronts the for-profit model, and instead offers a somewhat crude summary of the importance of open science during the pandemic, including preprints, open collaboration, data sharing and open access to research.

But at the time it was published, I remember the headline (likely the work of an eager subeditor) jumping out as pretty ridiculous. It seemed to betray gross ignorance about science publishing and especially how embedded commercialism is within the scientific process. Multinational commercial publishers control so much of the scholarly communication landscape that it is difficult to even entertain the idea of a time in which they do not dominate research dissemination. It’s hard to see the virus changing that.

Yet everything has been turned upside down since the end of February. Much of the world is now on lockdown and it is completely unclear how this will play out. As I mentioned in my previous post, COVID-19 has intervened in the publishing market in two quite unique ways: firstly by stimulating a reported culture of collaboration and open sharing aimed at rapidly combatting the virus; and secondly, with everyone on lockdown, by encouraging publishers to offer free content to aid online teaching. These seemingly unconnected issues are in fact related by the move to openness in a variety of forms.

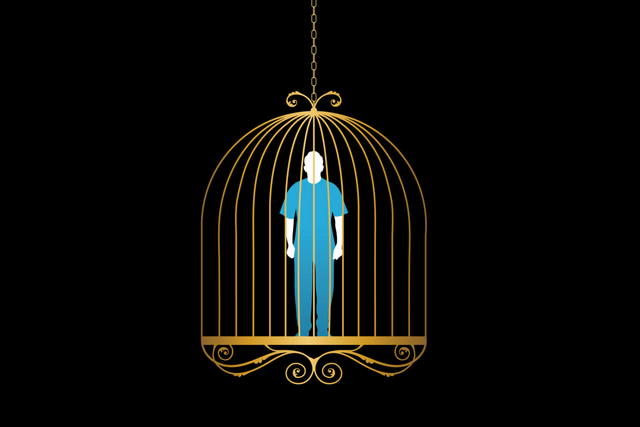

While it may be helpful, as Gary Hall has suggested recently, to think about the pandemic as an event in which we are ‘trapped’, and which therefore resists any hasty interpretation (paraphrasing Merleau-Ponty), I do still think there is value in trying to understand the possible impact of the virus on publishing – not out of any desire for certainty but rather to make visible the uncertainty of what’s going on. And with this uncertainty, we can ask if it is possible then that both the upsurge in open practices and the freely available content made available as a result of the lockdown might help nurture a better, more open and less profiteering publishing ecosystem?

To answer this question, it is first worth noting that the freely available content made available is largely done so at the behest of publishers and often in a piecemeal fashion, rather than systematically and in collaboration with authors, research communities and librarians. Jim O’Donnell, for example, has expressed scepticism that publishers are making content available purely out of altruistic reasons and are instead hoping to ‘entice users to some products they’ve not seen before and send those users back to their librarians insisting — when the free period is over — that we absolutely must subscribe to some of them — at a moment when prospects of budget flexibility are evaporating and cancelations are looming’. Even if this isn’t the case, it is important to note that paywalls have been lifted temporarily, unilaterally and unsystematically – purely in response to a global pandemic crisis. Once this crisis has passed, or at least when publishers deem it to have passed, there is no suggestion that anything other than business as usual will return and that paywalls will be re-erected.

But of course, economic business as usual will not return after the lockdown ends. We are likely heading for a depression, certainly a deep recession, and this will work against a diversity of academic presses who are able continue publishing. As Charles Watkinson, director of the University of Michigan Press, wrote recently on the Scholcomm list:

Most of us are presses who were already feeling the pinch of the declining market for monographs and the substitution of new purchases of course texts with secondhand and digital copies. This crisis and its aftermath will clearly push many of us even further over the edge at a time when our parent institutions will likely have bigger funding priorities to deal with […] There are many independent barely-for-profit publishers who are very similar to university presses and they will be feeling similar pain, without the protective umbrella of a higher education institution. The large commercial publishers, however, are generally more digital, more diversified, and more resilient and will be quicker out of the gate to vacuum up the reduced budgets that libraries will have.

If things were tough already for small, not-for-profit, and university press publishers, they are going to get worse during the downturn. Higher education is predicted to be badly hit by the crisis and this will have a knock-on effect on purchasing decisions, university press subsidies and overall budget availability.

Watkinson is absolutely correct that larger commercial publishers – the oligopoly – will be well positioned to take advantage of new economic conditions and will probably even further consolidate their sizeable market power. In controlling the majority of academic journals, these companies will be able to price journal packages in a way that makes them attractive to cash-strapped institutions, giving them a competitive advantage over the smaller publishers, not-for-profits, monograph publishers, and so on. Where open access is concerned, this will mean banging to the beat of the oligopoly’s drum, likely through increased transformative agreements, APC publishing and infrastructures that track researchers and monetise their data.

It is worth remembering that open access is now key to the business strategies of large commercial publishers who have figured out how to monetise subscription content, open access content and data analytics. For example, services such as GetFTR reveal a desire by the big publishers to collaborate with one another in order to keep users interacting on their platforms (rather than on institutional repositories, ResearchGate and Sci Hub). In doing this, user interaction data is made available – what Julie E. Cohen terms a biopolitical public domain – in a way that allows publishers to amass and exploit it for financial gain. This kind of data extraction is both a response to open access and a way to control it.

So COVID-19 does not ‘kill’ the for-profit business model decried above by Hiltzik and in fact might strengthen profiteering through the ability of the publishing oligopoly to weather the financial downturn and dictate the future of open access according to their conditions. While this might increase the amount of open access research available, it will be at the expense of the loss of control by the research community and the continued dominance of a handful of players. Such is the problem of a move to open access that is not emancipatory from capital, or at least antagonistic towards it.

Community-led open access

But what about our corners of OA projects and advocacy that are antagonistic to the profit motive or to the publishing oligopoly? How will radical, scholar-led and not-for-profit forms of open access be impacted by the fallout of COVID-19?

It is hard to avoid the fact that much of the OA movement evolved during a time of austerity. In the UK, our austerity programme began in 2010 and continued for many years thereafter (if it ever ended); open access gained popularity at the time, perhaps due in part to being part of this foment. At the height of this, OA advocacy was imbued with the sense that open access publishing is not just more ethical, but is also cheaper than traditional forms. Low-cost commercial publishers like PeerJ and Ubiquity Press launched in 2012 to offer inexpensive alternatives to the high APCs of commercial publishers, both of which are still going strong today.

Similarly, scholar-led and not-for-profit OA publishers have argued that their approach to publishing is cheaper to produce, either for journals or monographs. Many presses in the Radical Open Access Collective are entirely without remuneration and operate purely in the free time of those who staff them. Publishing can be done much cheaper but at what cost? OA has always had a difficult relationship with austerity and its tendency to devalue the skilled labour of those involved in the publishing process. While there is a nuanced conversation to be had about the costs of publishing (as the blogposts from OLH and OBP show) and the ways of valuing this labour, this conversation will be much harder to have during an economic depression in which there are continual pressures to ‘do more with less’. As much as scholar-led forms of publishing have real value and point to a future of scholarly communication controlled by research communities rather than commercial publishers, we must be careful at this stage to avoid arguing that all publishing should be managed entirely by working scholars (as I have argued elsewhere).

Now is perhaps a good time to re-inject politics into OA advocacy and to remind ourselves that open access only makes sense as part of a project to imagine a world beyond capitalism. It is thus emancipatory from the idea that knowledge and education can only ever be understood as a commodity and disseminated in a market; it recognises that there should be no financial qualification to either accessing or producing such knowledge, and that both could be supported through non-market and economically just means. Strategies for OA advocacy should therefore attempt to intervene in and unsettle the market where possible, while creating commons-based alternatives that point to a better future, such as AmeliCA, OPERAS and the COPIM project (among many others). Although none of what I’m saying is particularly new, it has never been more urgent.

One strategy to intervene in the market may take the form of governance, and COVID-19 is the perfect illustration of this. As publishers unilaterally decide which content to make available, should the research community not have a say in when and how they do this? After all, we create the content, though often in exchange for the copyright. Editorial boards should be able to demand a say over when content is made freely available and under what conditions, while librarians might request the same in their negotiations. These interventions in governance could form part of a broader strategy of increasing oversight by the academic community rather than governance by the market and control by commercial publishers. They may also allow us to retain ownership of our data and make commercial publishers accountable to researchers rather than the market at large.

This is why a systematic focus on governance – instead of, or at least alongside, open access – is vital for the future of publishing. Even if the for-profit publishing model is not going to be ‘killed’ any time soon, governance may still allow us to assert some control over it. Coupled with the publishing futures already being created and nurtured by library publishers, university presses and scholar-led collectives, we may be able to imagine a world that isn’t trapped in the logic of COVID-19.