The window has just closed for contributing feedback to Plan S, the policy initiative from a coalition of European research funders that seeks to mandate open access to funded research. Lisa Hinchliffe provides a helpful summary of the main themes and general trends from the feedback and it is not my intention to explore them here. However, after reading a number of responses from a range of interested parties (many of which saying the same thing in a variety of ways), I realised I’d lost sight of what the consultation was supposed to achieve. So what is the point of open access policy consultations?

At first glance, consultations are an opportunity for organisations and individuals to shape a particular policy intervention through their responses. The architects of Plan S have granted the public an opportunity to voice their concerns with the expectation that these concerns are both heard and taken onboard in the resulting policy. This reading appeals to liberal-democratic notions of governance that assume the correct way to proceed will prevail, or that a compromise can be reached, if people can air their grievances through open and frank exchange of ideas.

The problem with such a conception of policy consultations is that it isn’t entirely clear how they should work: Whose comments should be taken into account (and are they weighted somehow)? Who gets to speak for whom? How do the Plan S architects incorporate such divergent and often oppositional feedback? Put simply, it is unclear how such feedback could ever result in a representative and fair process if all responses have to be accounted for somehow. Policy consultations are thus not an exercise in radical democracy.

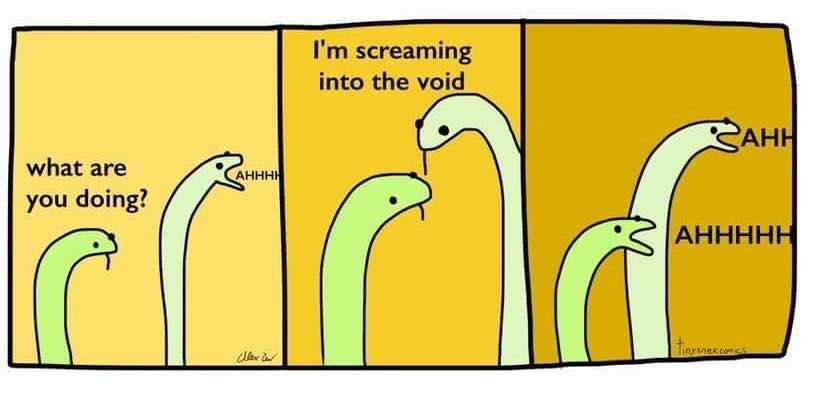

But, as Hinchliffe notes in the link above, some general themes have emerged from the consultation that (more often than not) express a general commitment to open access, openness and/or access but suggest improvements to the policy (both major and minor). But again, how does the coalition take this into account? Why are the views of some responders more important than others? How do they justify any subsequent changes to the policy as a result of the consultation? These questions are difficult to answer if one assumes that the consultation is anything more than mere lip service or screaming into the void.

In my PhD thesis, I looked at the creation of the HEFCE policy for open access for the next Research Excellence Framework. From reading a number of the consultation responses, and interviewing one of the policymakers at HEFCE, it became clear to me that the consultation was used to position actors in blocs so as to justify certain elements of the policy. For example, HEFCE were able to point to the consultation responses from learned societies and commercial publishers in order to make the case for a longer embargo length, even though many responses from different actors argued that embargos should be shorter. Learned societies and publishers were positioned by HEFCE as two different kinds of actors (the voices of academics and publishers) even though they both have a financial interest in the profits of the academic publishing industry. The consultation was thus used to justify (rather than reform) certain elements of the policy in accordance with the wishes of certain actors. The divergent responses to the consultation are helpful because they allow policymakers to cherrypick evidence that can make the policy more acceptable and seem more thought through.

From the perspective of cOAlition S, we might think of the policy consultation as an example of what Michael Callon termed interessement. In his influential article on the scallop fisherman of St. Brieuc Bay, Callon argues that power in a network works according to the extent that actors can successfully negotiate the interests of each other. They do this by problematising the issue at hand in such a way as to make it palatable to all actors in the network. Yet this is not a purely consensual process and operates according to different alliances and forms of exclusion. cOAlition S are thus able to point to the consultation responses of certain actors as representative of something broader, while simultaneously ignoring those of other actors. The consultation is most useful for the policymakers, then, as it facilitates this process (while simultaneously having the appearance of democracy in action).

Interessement also entails the need to speak on behalf of those who cannot talk. In Michael Callon’s case, this is the scallops that are subject to overfishing who cannot defend themselves verbally. In our case, however, it is the academics (among many others) who will be subjected to the policy even though they have most likely never heard of it and equally cannot voice their opinions. They are not disinterested in the policy even though they may be uninterested by or unaware of it. The consultation therefore allows cOAlition S to understand how the policy can be best framed so as to enroll the most important actors as allies to their cause and give it a sense of legitimacy. The consultation process is not necessarily about changing the policy, but about understanding how it can be made palatable to the most important ‘stakeholders’ that will be impacted by it.

This is not to say that the consultation responses aren’t useful exercises for those responding to it, but that they operate at the level of hegemony rather than rational argumentation and adjudication. The public airing of consultation responses is probably just as important as the feedback that is sent directly to the policymakers. cOAlition S are not interested in adjudicating on the common ground between all ‘stakeholders’, which is a fool’s errand put forward by commercial publishers hoping to maintain the status quo. Instead, political arguments need to be made as to whose interests are most important in scholarly publishing.

(image copyright Tiny Snek Comics).